HUMMINGBIRDS

Introduction to Hummingbirds

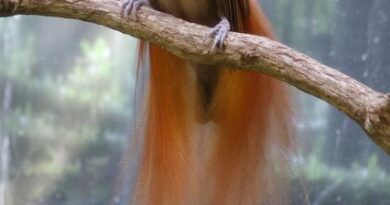

Hummingbirds are 319 species of tiny, fast, and active nectar-drinking birds of the New World, which take their name from the noise made by their incredibly rapid wingbeats. They feed on the wing and are related to swifts. Like them, they have very small legs and feet, used only for perching, and the bony structure of the wings is also very much reduced, with the greater part of the visible wing consisting of a large area of elongated primary flight feathers. The head is large in relation to the body.

Largest and Smallest Hummingbird Species

The largest, the Giant Hummingbird Patagona gigas of the Andes, is a little over 8 inches (20 cm) long, of which half is tail. The smallest, the Bee Hummingbird Mellisuga helenae of Cub., is the size of an insect. The body is about 1 in. (2–5 cm) long, with the bill and tail adding another inch to this. In the majority of species, the body size is 2 inches (5 cm) or less.

Unique Hovering Flight and Wingbeat Efficiency

The hummingbird has a problem associated with its mode of feeding. When taking nectar from blossoms, there is no convenient perch nearby, so it must hover while feeding, then move backwards to withdraw its bill from the flower. As a result, the flight is specialized. The wingbeat is highly efficient, and, proportionally, the hummingbird uses fewer beats than other birds. Some of the larger hummingbirds have a rate of 20–25 beats per second, comparable with that of the considerably larger and slower tits. In small hummingbirds, the rate rises to about 70 beats per second, but in giant hummingbirds, it is surprisingly slow, 8–10 beats per second.

Specialized Bills and Tongues for Nectar Feeding

The bill is long and fine, an exceptionally short one being only about half as long again as the head, while the longest, that of the Sword-billed hummingbird Ensifera ensifera is straight and as long as the head, body, and tail combined. Such a bill is designed for probing long tubular flowers. The tongue, slender and elongated, can be extended well beyond the tip of the bill, and the edges are rolled in to form a double tube up which the nectar is sucked.

Habitat and Migration Patterns

Many hummingbirds are forest dwellers, but they may occur in a wide range of habitats, extending into open country where flowering plants are present and also to high altitudes in mountain regions. In some cases, they are nomadic or subject to seasonal movements to take advantage of the flowering seasons of different plants. Several species are migratory, and three move into North America to nest in the southern parts of Canada or Alaska.

Display and Plumage of Male Hummingbirds

The displays of the hummingbirds are relatively unspectacular in terms of movement, usually being very rapid swoops terminating in a hover in front of the female, but the brilliance of the display lies in the vivid iridescent colors of the male’s plumage and the often eiaborate plumage decorations such as crests, ruffs, beards, and tail-streamers. Most of the more vividly iridescent plumage is on the throat and crown-brilliant shades of red, yellow, pink, purple, blue, or green. In many cases, this is only really conspicuous from one angle, usually from the front, so that it shows to the best advantage when the male hovers before the female. The head color may be enhanced by decoration such as the long, tapering green or violet crests of the plovercrest Stephanoxis, the green and red paired horns of Heliactin cornuta, or the black and white paired crest and pointed beard of Oxypogon guerinii. In addition to a bright crest, the coquettes of Lophornis have erectile fan-shaped ruffs on the sides of the neck, boldly colored, and contrasting bars or spots at the feather tips. When the male hovers before the female, the other visible parts of the plumage are the undersides of the wings and tail. The body plumage of most hummingbirds is glossy green or blue, and the underwings may have a contrasting chestnut-red tint. The tails of some show an overall bronze or purple iridescence on the undersides of tail feathers, visible in display but not obvious from above, while on others the feathers may be tipped, streaked, or blotched white. In addition, the tails may have a variety of shapes. Broad fans are frequent, and forked tails vary from blunt forks to the long scissor-shapes of the trainbearers Lesbia and the slender tail streamers of the streamer-tail Trochilus polytmus. Others show different degrees of tapering and elongation of the central tail feathers, as in the hermits Phaethornis.

Nesting and Reproduction in Hummingbirds

The nests are built of fibers, plant down, and similar fine material, as well as moss and lichen, bound together with spiders’ webs. Some are smooth, neat cups on twigs; others are domed; and some are pendent, or built onto hanging plants. They are often decorated externally with lichens. The female builds the nest, incubates, and cares for the young. She lays two white eggs, which are large in proportion to her body and bluntly elliptical. Incubation takes about a fortnight, and the young are born naked. The female feeds them by inserting her bill well into the chicks’ gullets and regurgitating food. The young take three to four weeks to fledge, the period varying, apparently in response to the food supply available. FAMILY: Trochilidae,

ORDER: Apodiformes, CLASS: Aves.